High-intensity interval training (HIIT) has gained significant attention from practitioners in professional football over the past few decades. It is widely used as a powerful tool for enhancing players’ running abilities to meet the demands of modern matches. HIIT enables coaches to target key physiological adaptations through time-efficient formats and often tailored to the sport or even specific positions. Professional teams employ various HIIT formats to develop and maintain players’ aerobic capacity from the off-season and pre-season to the competitive phase. By adjusting parameters such as duration and intensity, coaches aim to achieve optimal results. With long-duration, marathon-style runs now a relic of football’s past, this brief review explores current practices, focusing on the most common running-based HIIT formats used in football today.

By quickly simplifying Laursen & Buchheit categorization from Science and Application of HIIT, we can understand HIIT formats at our disposal:

1. Long intervals

Usually 2 to 5 minutes in duration, using intensities approx. 80%VIFT or 90-95% vVO2max, with active or passive recovery. Work-to-rest ratio 2:1-1:1.

2. Short intervals

10-60 seconds in duration, covered at supramaximal vVO2max speeds, ranging from 90-105% VIFT or 100-120% vVO2max, with mostly passive rest; W:R ratio 1:1-1:2.

3. Repeated-Sprint training (RST)

Usually, all-out intervals are covered in 4-10 seconds, with passive rest, W:R ratio ranges widely from 1:1 to 1:6 or more.

4. Sprint interval training (SIT)

All-out efforts with prolonged duration, usually 20-30 seconds with longer passive rest.

5. Small-sided games (SSG)

Widely used in team sports with an idea to integrate physical, technical & tactical work, thus saving time and providing very sport-specific stimuli. Mostly using from 3v3 to 6v6 player ratio, with duration similar to long intervals.

Just by looking at potential solutions for our training puzzle, we note that different options might hit different physiological targets like aerobic and anaerobic energy contribution, and neuromuscular strain. At the same time, practitioners would agree that not all formats have the same value when used in professional football. With different cost-to-benefit ratios, and ranging from sport-specific to very distinct from modern football needs, we have to choose the most appropriate tool to tick our training checklist. It is worth noting that, just by tackling different parameters, we can highly change training stimuli applied even within any given format. With so many degrees of freedom in mind, the aim of this blog is to briefly consider the most suitable formats, widely used in football.

In order to make this post simple and very straightforward, using available literature and personal experience, let’s walk through a couple of ideas regarding every format.

Long intervals (LI)

This HIIT format received a lot of attention in the past, mostly back in the days when team sports started “outsourcing” S&C coaches coming from athletics. With being time and energy-consuming, LI might have their place in a very specific time of yearly planning, like (1) longer off-season periods, (2) early in the pre-season during the general preparation phase (GPP), and (3) in rehabilitation protocols where the player is coming back from a longer absence.

Using lower running intensities, and if programmed without change of direction (COD), LI could be a viable tool when introducing mid to higher running volume, without putting too much strain on running musculature, while building aerobic endurance. Lower speeds are related to lower hamstring strain, and the absence of COD might decrease quads and glutes strain. On the other side, when used with intensities closer to vVO2max, LI might provoke higher rates of anaerobic energy contribution, which might be an important consideration when choosing this format.

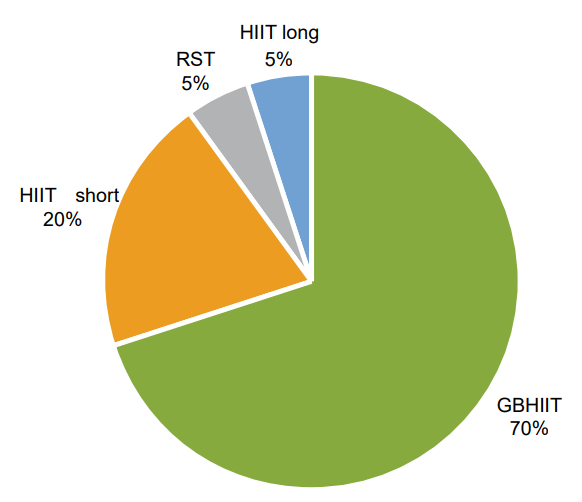

With a very low total contribution to HIIT used in football (5%) reported by Laursen & Buchheit, LIs do not represent a widely used conditioning tool in modern football. With a prolonged competition phase and a very short off-season at the elite level, LIs are used only to cover individual needs in a very specific context. A good example would be mid- and end-stage rehab protocol, where progressing with running volume is the main topic of the session since the player is not able to participate in game-based drills. With long duration and high energy costs, S&C and football coaches are looking for other formats that might be used for top-up team conditioning, thus leaving more time for technical and tactical drills.

Example protocol:

5×3′ @80-82% VIFT with 1.5′ passive rest (total time 21′)

Short intervals (SI)

SIs represent the most widely used type of HIIT in team sports, specifically football. Short in duration and easy to implement in team settings, SIs are used during all training phases year-round. Besides SSG, SIs are used as the main conditioning stimuli in pre-season, and a powerful top-up tool at team and individual levels in the competition phase. Using higher running intensities, SIs allow coaches to implement HSR in a daily routine if that is the target, and include higher muscle strain with adding more COD. Modifying duration, intensity, and rest periods, SIs allow practitioners to hit different physiological targets, handling anaerobic energy contribution and neuromuscular strain. Since it is considered a very powerful weapon, it comes with great responsibility. Optimally combining football sessions with SI requires detailed planning and load monitoring on a daily and weekly level.

Different types could be introduced on any given day of the week, with the proximity of the next/previous match in mind. However, when talking about the most common practices in football, SIs are usually used:

- Mid-week, where aerobic conditioning represents the main session theme. Usually in team settings, individualized using previous testing values. Might be a pre-planned team drill, or used with a specific group of players (not hitting desired/planned volumes in game-based drills, or as a top-up for players with fewer playing minutes or coming from injury)

- As an individual or group top-up in subsequent sessions, if planned targets are not hit early in the week. This should come with a high level of cautiousness since it might interfere with readiness for the end-week match or other training theme of the day (concurrent training).

- As an individual top-up for players who are in advance excluded from end-week matches (suspensions, tactical reasons). This might be a key strategy for optimizing the training load for players with fewer playing minutes.

- As a part of the compensation protocol post-match and on MD+1, where coaches try to hit many targets with a single hit, thus using formats that will include high-intensity running, high-intensity acc/dec, and COD.

We can conclude that SIs have daily applications in football. Passive rest allows us prolonged quality work in subsequent reps, without training to exhaustion, thus allowing more time spent at VO2max. It is interesting to note that shorter set duration can provide significant effect, especially when SIs are incorporated in team football sessions, thus not affecting the quality of technical work that has to be done. Using team meetings to introduce the top-up concept to players might increase buy-in and highly affect the quality of the session.

Example protocols:

1. 2×8′ 30s @90% VIFT with 30s passive rest, 3′ passive rest between sets (pre-season example, total time 19′)

2. 2×4′ 15s @95% VIFT with 15s passive rest, 2′ passive rest between sets (in-season top-up example, total time 10′)

Repeated Sprint Training (RST)

This format of HIIT implies all-out, max effort, and thus doesn’t need testing and further individualization. Being very intensive in nature, RST is rarely used in the competition phase as a team conditioning tool. Furthermore, it has a place (maybe) in the last phase of pre-season and in very specific contexts like tackling non-starters’ workloads and in very late-stage rehab protocols where players are introduced to worst-case scenarios. Precisely planning these activities can not be stressed enough, since it is very easy to accumulate a very high amount of sprinting, especially in a very short time (sprint distance per minute).

Many practitioners completely exclude this type of work and focus on using different tools for improving aerobic conditioning, while implementing other strategies to introduce sprint to their programs (more traditional speed training with long and complete rest). The basic idea behind it is that improving aerobic conditioning and MSS separately might result in a subsequent increase in RST ability. From a personal experience, I can say that I used this type of work occasionally in the second phase of pre-season, but recently completely excluded it from my program.

In the case of using RST, some things have to be considered. While the straight-line format will introduce a huge amount of sprint, thus putting a significant load on the hamstrings and eliciting injury risk especially in fatigue state during final repetitions, other formats could be used to hit other targets. Adding more COD will introduce a higher mechanical load, without hitting very high speed, which might be a very valuable option when trying to compensate lack of playing minutes.

Example protocols:

1. 2×3′ 5s Vmax straight line with 25s passive rest, 3-4′ passive rest between sets (or longer active rest) (total efforts 12, total time 9-10′)

2. 2×3′ 5s Vmax with 2COD (180 degrees) with 15s passive rest, 3-4′ passive rest between sets (or longer active rest) (total efforts 18, total time 9-10′)

Sprint Interval Training (SIT)

Considering the risk-to-reward ratio, this HIIT format is completely excluded from conditioning programs in football. When looking from a sport-specificity perspective, this amount of continuous all-out effort will never happen in a football match. Additionally, the strain on the locomotor apparatus, especially hamstrings is extremely high, and the risk of injury is highly increased. By looking at Laursen & Buchheit’s chart (above), we can see that S&C practitioners don’t have this tool in their toolbox when it comes to conditioning football players. Although personally aware of the presence of this format in football settings around the world, I highly recommend using different strategies.

Game-based HIIT (Small-sided Games – SSG)

SSGs represent the majority of HIIT work in professional football. Practitioners have an opportunity to play around with different parameters in their pursuit of highly game-orientated conditioning. Although SSGs are out of the scope of this blog post, it is important to point out a couple of key parameters. SSGs include different numbers of players, usually in small ratios from 3v3 to 6v6, using different pitch dimensions and game rules. Coaches usually use area per player (APP) to describe SSG (length x width / total No. of players), considering it a key parameter when prescribing SSG from a conditioning point of view.

Although APP truly is a key parameter, many other parameters might affect the final outcome (presence or absence of GKs, verbal cueing from coaches, motivation, rules like number of touches, orientation of the pitch – square vs rectangle, and many more). Thus, SSGs are, like football itself, chaos in nature, and by definition, chaos is something that is out of control. So, SSGs although very nice as an idea have some limitations. It is noted that very well-trained athletes might not reach sufficient intensity during SSG (>90 or 95% of VO2max). Furthermore, most talented players might present a significantly lower level of total workload, simply because of their better positioning, body orientation, decision-making, and anticipation, which might wrongly characterize them as “lazy” or at least “not working hard enough”. Some limitations are described, but without losing focus on the positive sides, like including highly sport-specific stimulus, hitting many targets at the same time, and very high buy-in from players.

From a personal experience, I truly believe in the optimal ratio between game-based and running-based conditioning, since the latter gives us very precise, controllable, and individualized stimulus, making sure that we indeed hit the target once the session is over. With that in mind, we can program a mix of SSG and running HIIT, covering the limitations of both approaches. For example, using live tracking during SSG and defining players that need top-up running could be just one option.

For additional information on using SSG in the physical preparation of football players, I highly recommend Andrea Riboli’s work. Andrea spent more than a decade in Italian Seria A, working for both AC Milan and BC Atalanta, and has very extensive knowledge on this topic. In the end, quick thanks to Paul Laursen, Martin Buchheit & Andrea Riboli for generating and sharing knowledge in this area.